For My Family, Bridging the Generation Gap Is a Journey of 7,000 Miles

By Taylor Zhang, Class of 2016

My dad used to tell me I took things for granted, especially on my birthday or Christmas. I always thought he was just a party pooper. But of course, you should never ignore what a wise Chinese man has to say.

The conversation would go somewhat like this:

“Thanks for the math book, Dad.”

“You should be more grateful. When I was your age, I didn’t have math books to study. In fact, I didn’t even have cake when I was your age, not to mention the things to make a cake. Eggs? Oil? Yeah, right. When I was your age, I got a hard-boiled egg for my birthday. And that was only because our neighbors were nice!”

He would lecture me continuously about the past and the opportunities I had. But it wasn’t until more recently that I began to take an interest in my parents’ past.

Shu Zhong Zhang, my father, was born in 1947 in Xi’an, China. Grandpa was a registered Nationalist supporter, and when Mao Zedong’s Communist Party took over in 1949, Shu’s family was in a bad situation. My grandpa was promptly fired from his job. Communist China was an underdeveloped nation, and my grandpa’s Nationalist affiliation made it even harder to find any opportunity for steady income.

There was no meat, no electricity, no heat, no air conditioning and no space. Shu’s house was about the size of a small hotel room. He shared living space with his parents and four siblings. When it was cold, it was really cold. When it was hot, it was really hot. When it came time to eat, there was always something to eat, but it wasn’t much. Vegetable soup was served daily; on a good day there were some potatoes. Meat was out of the question, and if there was some “quality” food, it usually went to the eldest members of the family.

Conditions worsened when the Great Leap Forward was put into action by the Chinese government in the 1950s. The program essentially caused economic regression and claimed many lives in the ensuing famine. My father, however, endured. During the famine he was forced to start laboring as a 12-year-old in order to make enough money for food. His jobs ranged from mixing concrete to working in construction. The work brought meager amounts of food, still better than nothing.

On top of working to help feed his family, he attended school every morning. He was found to be proficient enough to earn an apprenticeship in making glassware. He moved into the glassware factory with his father, who also finally found work there, while the rest of the family moved to a rural region where food was easier to come by.

My father continued schooling and his apprenticeship while working in the glass factory. His grades were great, and higher education would have been a real possibility if not for his status as a relative of a Nationalist supporter.

The Cultural Revolution began in 1966, right around the time my father finished his apprenticeship and began full-time work. These were dangerous times. Any political dissent was punished by violence. Shu was lucky not to get caught up with the revolution, but he did not escape its horrors. He regularly saw political opponents dead in the streets. During periodic marches for the “great chairman Mao,” people who were found to be “against the revolution” would be forced to dance and sing praise to the glorious leader. Shu stayed out of all that.

His mother suffered a stroke, leaving her essentially paralyzed and unable to feed or take care of herself. By that time Shu’s father was too old to work. All of Shu’s siblings had married and moved away; Chinese culture dictates that one of the children must take care of their parents, and this responsibility was thrust upon my dad. For 20 years he went to work in the morning, went to the market, and went home to feed his parents.

“Chinese culture dictates that one child must take care of the parents, and this responsibility was thrust upon my dad. For 20 years he went to work, went to the market, and went home to feed his parents.”

My mother, Ke Ming Li, was born in 1958. She grew up in Anhui province as a farmer and also lived through poor conditions during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. Luckily, her grandfather, a professor in America, was able to obtain visas for her family to go to America. Her grandfather had gone to school with several Communist Party members and had connections in the Chinese government. In America my mother, her siblings and her parents began working in restaurants, eventually opening their own Chinese restaurant in the 1980s. It was during this time that her family met my father’s older sister, who set up the marriage of my parents. They married in 1986 and had their first child in 1987. The marriage took place in China, and while my mother came back to America, my dad stayed to continue to care for his mother. When she died in 1986, he immigrated to the United States.

The quality of life in America was, of course, exponentially better. But to the average American, it was still pretty bad. They both worked six days a week, 12 hours a day, for less than minimum wage until they sold their first restaurant. To make things worse, their first child, my sister Diana, died in a car accident when she was only 6 years old.

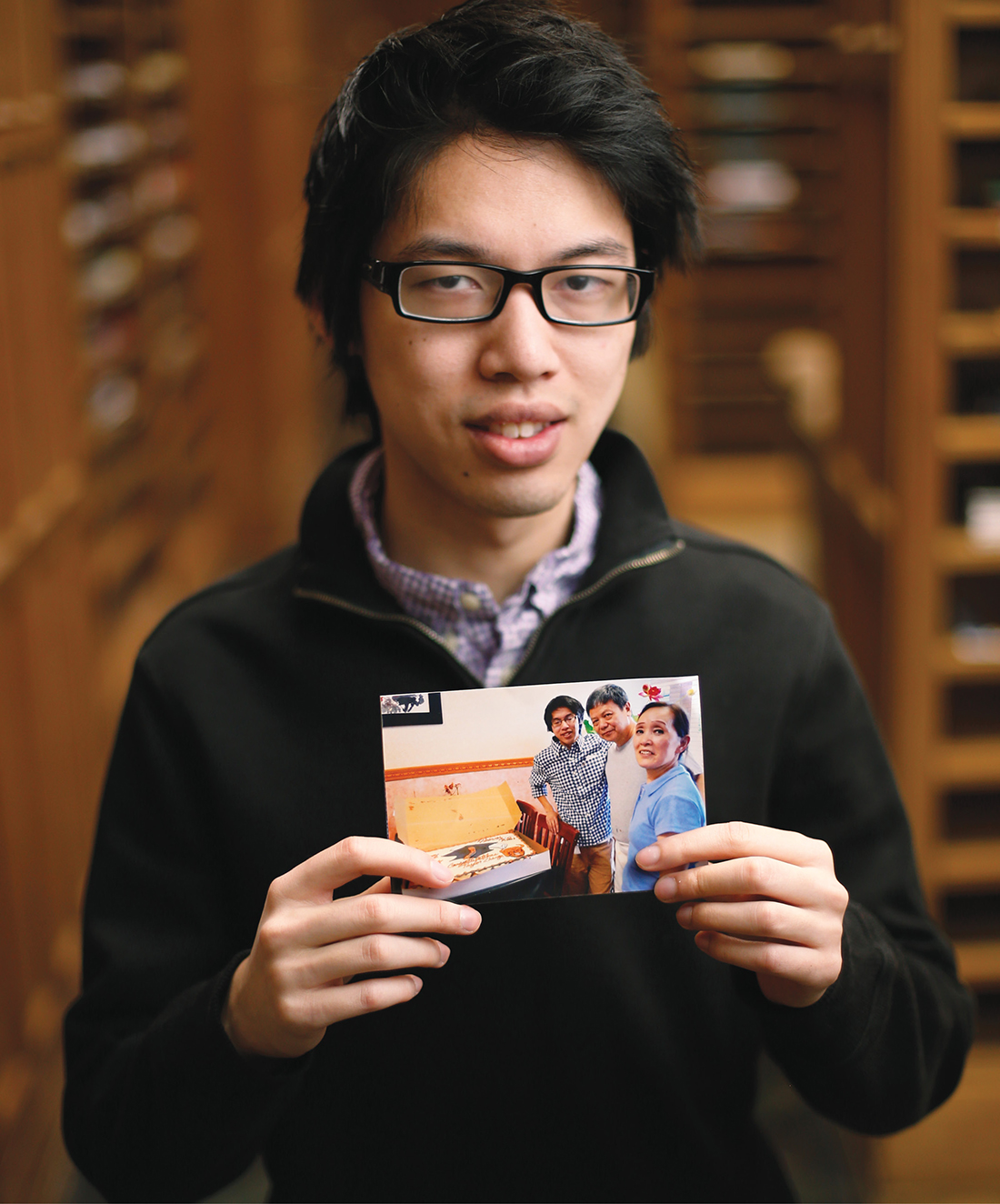

I was born in 1994, and my parents still haven’t stopped working. They now own a small Chinese restaurant in North Canton, Ohio. They run the business by themselves with no employees (except for me), 12 hours a day, seven days a week. My dad is 65, my mom 55. All their lives they’ve worked, but for what? Time is running out.

If life were a poker game, my parents were dealt a terrible hand, one that entailed a long and tired journey. They have told me repeatedly that I am their one motivation. Sometimes it’s like a stuck record, but they speak the truth. My parents live vicariously through me. It is a tough relationship. If I fail at something, then I have not only failed myself but my parents, too.

I understand this is stereotypical for a Chinese son to have these feelings, but how could anyone not feel this way? After everything my parents have been through, failure cannot be an option. I strive for excellence, and I do it not just for myself, not because I am Chinese, but for those who have given me everything.

When I do actually succeed, it means the world to my mother and father. When I have done something great, they have also done something great. At my high school graduation, when they watched me deliver my salutatorian graduation speech and saw all those people clapping for me as I was handed my diploma, they could not have been happier. I could not have been happier for them.

Since the small Chinese restaurant business isn’t particularly lucrative, my attendance at Vanderbilt was only made possible through Vanderbilt’s financial program and the incredible generosity of the DeMartini family who supported my scholarship. These philanthropic efforts have given me a life-changing opportunity, one that my parents and I are grateful for receiving. And now that I am at one of the greater learning institutions of the world, they happily tell others I am enrolled at Vanderbilt.

If you ever happen to stop by the Tasty Garden in North Canton, Ohio, enjoy your food and tell my parents to take a break. They certainly deserve one.

Taylor Zhang, a sophomore chemistry major in the College of Arts and Science, is the recipient of the DeMartini Family Scholarship. Watch this video to learn more about the impact of Opportunity Vanderbilt, the university’s undergraduate scholarship effort.