BY JOANNE LAMPHERE BECKHAM, BA’62

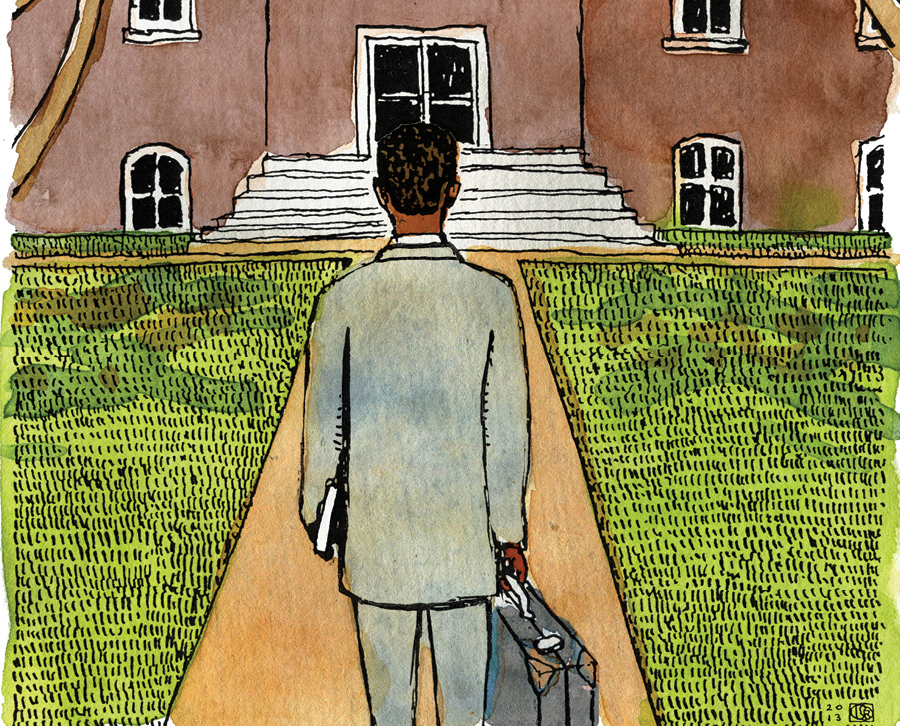

Nearly 50 years ago Robert J. Moore watched the countryside pass by his window during a long bus ride from Richmond, Va., to Nashville. As he traveled west, Moore wondered how he would be received as one of the first African American students to attend Vanderbilt University’s undergraduate schools.

What he found was a challenging, often lonely, ultimately rewarding experience.

“My family was very poor,” says Moore, BA’68. “Attending Vanderbilt on a full Rockefeller Scholarship was the chance of a lifetime.

“I knew there would be a range of acceptance and rejection. Some people were ugly, some gracious and fair-minded. Most left me alone, and that was OK.”

While Vanderbilt gradually began integrating its graduate schools as early as 1953, the undergraduate schools remained primarily white and male until the early 1960s. In February 1962, 60 percent of the undergraduate students voted against integration. Nevertheless, that May the Board of Trust voted to open all Vanderbilt schools to qualified students of all races. In the fall of 1964, eight remarkable African American students made history by enrolling in the College of Arts and Science and the School of Engineering.

It was a tumultuous time in American life, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and an escalating war in Vietnam. Televised reports of racial violence and assassinations intruded on the peaceful campus scene. Just two months before the black students arrived on campus, President Lyndon B. Johnson had signed the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed racial segregation in the nation’s schools, workplaces, and public accommodations such as restaurants.

“There was a lot of tension on campus,” says retired attorney Gregory Tucker, BA’68, MMgt’71, who is white.

Some of the first African American undergraduates came from poor families. Others had parents who taught at Nashville’s historically black colleges and universities. All were ranked at the top of their high school classes, having grown up in supportive, though segregated, communities in which teachers pushed their best students to succeed. Isolation from those communities proved to be one of the biggest challenges they would face at Vanderbilt.

While the university was hardly a hotbed of overt prejudice, “it was extremely conservative in its racial views and decorum,” says Tucker, former editor of the student newspaper, the Vanderbilt Hustler. Most white students and faculty members wanted to be decent and fair, with many supporting the idea of integration. However, vestiges of segregation, such as all-white sororities and fraternities that dominated campus social life, remained. African American alumni recall professors making “gratuitous racial comments” in class and some white students brandishing the N-word as an epithet. When black students went through rush, Moore remembers, some white brothers refused to shake hands.

A few students like Moore and Tucker had friends of both races, but such friendships were rare. Even when sought, relationships between blacks and whites could seem forced and awkward. Black students often felt isolated, lonely and angry. “Isolation from the [larger] black community was the hardest thing I experienced,” Moore says. Until the first African American faculty members, James P. Carter and Malinda H. Gregory, were hired in 1965, students had no professional black role models.

“It was a difficult but ultimately rewarding experience,” says Dorothy Wingfield Phillips, BA’67, the first black woman to receive an undergraduate degree from Vanderbilt. The daughter of a Baptist minister, Phillips grew up in an activist family. Her older brother took part in the Nashville sit-ins, and her family was among the first to integrate a Nashville neighborhood.

Phillips transferred from Tennessee State University in January 1966 with close to a 4.0 GPA. A chemistry major, she went on to earn a Ph.D. in biochemistry in 1974 from the University of Cincinnati. She recently retired as director of strategic marketing for Waters Corp., a laboratory analytical instrument and software company in Massachusetts.

“There were very few of us, so it was kind of lonely. It was challenging academically and also in some of the attitudes I encountered,” Phillips remembers—from faculty as well as students. “I learned about myself and what I can do against obstacles.”

Diann White Bernstein, BA’68, had an easier time than some of the other black students. “It was a wonderful experience that made a difference in my life,” she says.

One of 10 children, Bernstein was the first in her family to go to college. Valedictorian of her high school class, she attended Vanderbilt on a Ford Foundation Scholarship. As a freshman living in Branscomb Quadrangle, Bernstein says she felt supported by both her roommates and some of the other white students. She gratefully recalls a math professor and a guidance counselor who steered her to a successful career as a psychiatric social worker and parole agent. Bernstein retired in 2004 and makes her home in Upland, Calif.

Bernstein notes that she probably had a more positive experience than her male counterparts. “Black females have always been less threatening to whites than black males,” she says.

Chancellor Alexander Heard was openly supportive of the black students. “He listened to us and encouraged his staff to listen, too,” says Moore, a child protection attorney and former high school English teacher who lives in Connecticut.

Heard garnered his share of criticism in 1967 when riots broke out in North Nashville the night after Stokely Carmichael, a leader in the Black Power movement, and Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at Vanderbilt’s Impact Symposium.

The black students also found allies in faculty members like English professor Vereen Bell. “His ancestors owned slaves, but I could be very candid with him,” Moore says. “He was genuine.”

Among the other African American pioneers was Conra Gandy Collier, BA’68, who lives in Brentwood, Tenn., today. The daughter of academics, Collier majored in French and earned a master’s degree in computer science in 1971. Her brother-in-law, the late Dr. Maxie Collier, BA’67, transferred from Tennessee State to Vanderbilt in 1965 to study chemistry and went on to earn his M.D. at another university. Earl LeDet, BE’68, and Norman Bonner, ’68, are also deceased. Bonner and William Randolph Bradford, ’68, left Vanderbilt after their freshman year.

In order to provide mutual support and problem-solving, black students formed the Afro-American Association in 1967, much to the chagrin of the Vanderbilt Hustler, which was lobbying for an end to the segregated fraternity system. The newspaper believed the African American students were moving in the wrong direction, away from an integrated campus, Tucker recalls. “We were negative on separate but equal,” he says.

One month before graduation in 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis. Riots broke out across the nation, tanks rolled down streets near the Vanderbilt campus, and martial law was declared in Nashville.

“I remember walking across campus and hearing a student say, ‘Martin Luther King has been shot,’” Moore says. “I went to my room in Barnard Hall, shut the door, and stayed there all night. I felt very vulnerable. One of my friends came to tell me that some of the students and Beverly Asbury, Vanderbilt’s chaplain, were planning to march downtown the following day. I was president of the African American Student Association and knew I needed to lead that march, but I worried about leading it in the right way.

“We marched several miles to a church, and when I looked back at the marchers, I saw white students, too,” Moore recalls. “I realized they were marching because they wanted to. I was impressed and humbled.”

The first African American undergraduates at Vanderbilt experienced rejection and acceptance, loneliness and mutual support. Most were willing to be pioneers of racial integration because they had a higher purpose. “I was at Vanderbilt for a reason,” Moore says. “I was determined to get a degree from a major university. I also represented a community, a village.”

Joanne Lamphere Beckham, BA’62, worked as an award-winning editor at Vanderbilt more than 25 years. Since retiring from a full-time career in 2006, she has continued writing for various publications and has taught English as a Second Language. At Vanderbilt she earned her undergraduate degree in English, cum laude, and did graduate work at Peabody College and the Owen Graduate School of Management.

Visit the Bishop Joseph Johnson Black Cultural Center website.