By Andrew Maraniss, BA’92

They walked up to us, one by one, for nearly two hours, many of them with tears in their eyes. Then they looked at the man seated next to me, clasped his hands, and spoke from the heart.

I’m sorry for what you went through. I could have done more to help. I should have known. I wish I had known. I admire your courage. Thank you for being here tonight. You’re a hero. I’m proud of you.

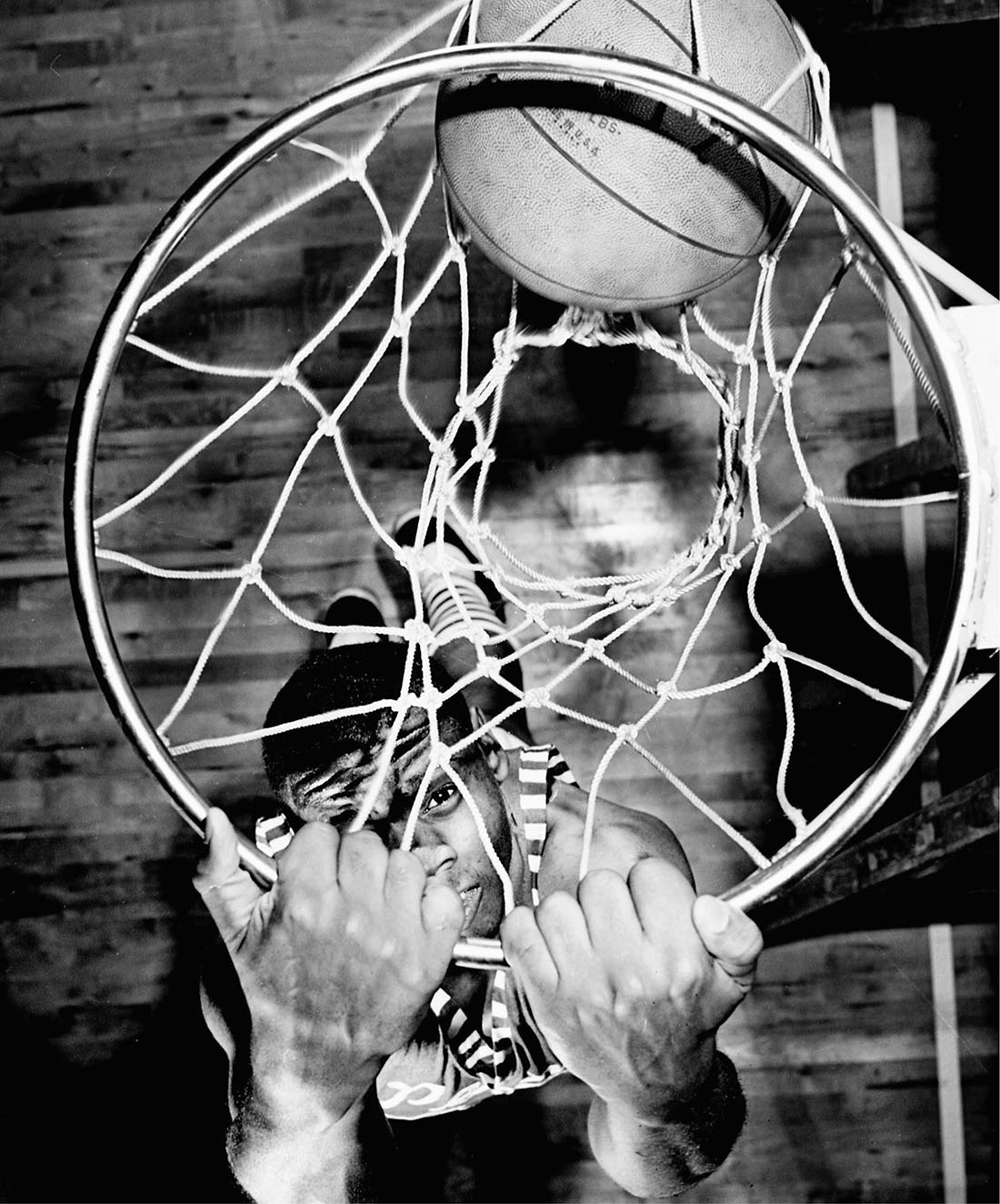

The man sitting next to me on the night of Dec. 3, 2014, was Perry Wallace, and many of the 400 people approaching him were fellow Vanderbilt alumni, including members of Wallace’s Class of 1970. It was an exhilarating and emotional scene at the Nashville Public Library, the official launch of my biography of Wallace (Strong Inside), the first African American basketball player in the Southeastern Conference. As we sat together and signed books after an hour-long Q&A before an overflow crowd, it was heartening to see Wallace embraced and loved again in the town in which he had grown up, gone to school and made history—the same town he was run out of 45 years ago.

For it was in March 1970, a day after his final game as a Commodore, that Perry Wallace spoke the truth to The Tennessean about his experiences on campus, around Nashville, and in the small college towns of the SEC. He had a moral obligation, he believed, to talk frankly about the challenges—the racism—he had endured as a pioneer, so that those who followed him, and the Vanderbilt community as a whole, could learn from his experience.

He suspected that reaction to his words would be severe, that most white Nashvillians and many members of the Vanderbilt community would not want to hear what he had to say, and he was right. Former Tennessean editors John Seigenthaler and Frank Sutherland told me the phones rang off the hook at the paper the day Sutherland’s story ran, Vanderbilt fans calling to cancel their subscriptions and calling Perry Wallace ungrateful. In effect, Wallace said, by telling the truth he had “written his ticket out of town.”

You can be treated well, you can be treated badly, or you can be treated not at all—completely ignored, denied your very humanity.

I was about 2 weeks old, born to students at the University of Wisconsin, at the time Wallace gave that interview to The Tennessean. It was 19 years later, in the fall of 1989, early in my sophomore year at Vanderbilt, that I first saw the name Perry Wallace, in a magazine article that described his first harrowing game at Mississippi State. Having arrived at Vanderbilt on the Fred Russell–Grantland Rice sports writing scholarship and majoring in history, I was captivated by a story that brought together my loves for sports and history.

I called Wallace—at the time a law professor at the University of Baltimore—and interviewed him for a term paper for my Black History class. Wallace was patient and kind, explaining to a naïve kid why he had approached road trips through the Deep South with the “deepest sense of dread” (he thought he might be shot on the court or around town before a game), and what it was like to be cheered on the Memorial Gym court and largely ignored off it. Professor Yollette Jones gave me an ‘A’ on the paper, and I felt a boost of confidence in my ability to succeed as a Vanderbilt student—and a special attachment to Perry Wallace and his story.

But it wasn’t until the fall of 2006, 14 years after I graduated, that it occurred to me that I wanted to pick up where I had left off in college, to write a serious biography about an important and underappreciated figure in the history of American sports and civil rights. I emailed Wallace, by then a law professor at American University.

“Do you remember me? I’d like to write a book about you. Would you be willing to do all the interviews it will take to do this right? What do you think?”

Wallace said he did remember me, that I should ‘go for it.’ The next day I got in touch with his old Vanderbilt basketball coach, Roy Skinner, and arranged an interview. I ended up speaking to more than 80 people for the book and became a regular at the Vanderbilt library and its special collections archive, scrolling through microfilm and digging through boxes of letters and memos, all part of a research phase that took nearly four years. Actually writing the book—a process happily interrupted by a wedding, a move, and the birth of two kids—took another four years.

Through it all, Wallace remained a forthcoming and wise teacher, telling me not just about his own life experiences but sharing a nuanced view on the South, on the daily realities of integrating a campus, and on race relations.

Wallace told me that one can be treated in any of three ways: You can be treated well, you can be treated badly, and you can be treated not at all—completely ignored, denied your very humanity. Wallace experienced a bit of the first at Vanderbilt; there were administrators, professors, students, alumni and teammates who treated him well. But there were more than enough ugly incidents, and far too much of the isolation, to prevent his pioneering journey from being the neat little success story many people have always wanted it to be.

That’s why the reaction during my book launch at the library, the outpouring of emotion, was so significant. Wallace told me that when he gave that interview to The Tennessean in 1970, he believed that even though most people at the time wouldn’t want to hear what he had to say, he had enough of a sense of history—and enough hope that attitudes would change in the future—that someday people would understand and appreciate his words.

We often think of progress being embodied by new generations, a fresh wave of young people unburdened by some of the hang-ups of their parents and grandparents. And in Wallace’s case, that is true—there is a new generation of students bent on social justice. But what was so beautiful about the scene at the library that day, and so many similar scenes in the days that followed, was that the change Wallace had been waiting nearly a half-century for was playing out in the hearts and minds of his own contemporaries. I couldn’t have been prouder to be a Vanderbilt man that night—incredibly proud of the courageous man sitting next to me, and proud of the older alumni who stood in line for two hours, looked Perry Wallace in the eyes, and told him, in so many words, that they loved him.

It was the best Vanderbilt homecoming I’ve ever seen.

Andrew Maraniss, BA’92, is a partner at McNeely Pigott & Fox Public Relations in Nashville and author of the New York Times best-selling book Strong Inside: Perry Wallace and the Collision of Race and Sports in the South, published in 2014 by Vanderbilt University Press. For more about the book, visit andrewmaraniss.com and follow Andrew on Twitter @trublu24.