Poor moms who return to the workforce after a period of unemployment suffer significantly higher rates of depression, anxiety and physical symptoms of stress when they don’t have access to decent childcare, according to new research led by Vanderbilt sociology graduate student Anna Jacobs.

The study, “Employment Transitions, Child Care Conflict, and the Mental Health of Low-Income Urban Women With Children,” was published online June 22, and will be the Editor’s Choice selection in the July/August issue of Women’s Health Issues.

Much of the research on labor and health shows that having a job is generally good for you, said Jacobs, who studies labor law and policy. “We were interested in finding out whether that was always the case, and when employment might not be beneficial.”

Using longitudinal data from a series of Welfare, Children, and Families project surveys in Boston, Chicago and San Antonio, the researchers tracked the employment status and mental health of about 2,000 unemployed urban mothers and grandmothers raising at least one child under five from 1999-2001. During that time, approximately 38 percent of these women became employed, either on their own or as a condition of their welfare benefits.

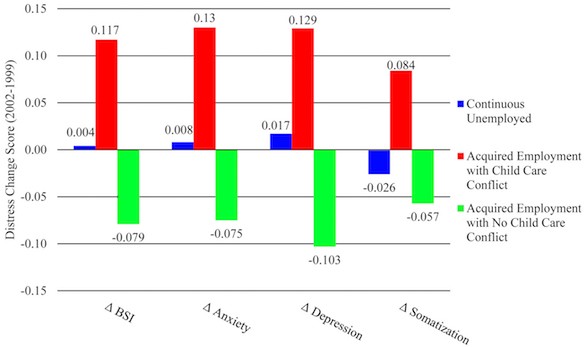

As expected, the researchers saw a considerable improvement in the women’s mental health—but only for the approximately 80 percent who reported no problems arranging childcare.

For the remaining 20 percent who did experience childcare conflicts, the opposite occurred: Not only did their mental health not improve, it got worse. In fact, these women saw their mental health decline nearly as much as the mental health of women without childcare problems improved.

Jacobs says it’s clear that a lack of childcare can significantly undermine the benefits of work. And while the data are old, welfare and workfare have not changed much since those surveys were first conducted. She and her colleagues conclude, “Policies that focus on moving low-income women off of government assistance and into paid work could be more effective if greater resources were devoted to quality childcare.”