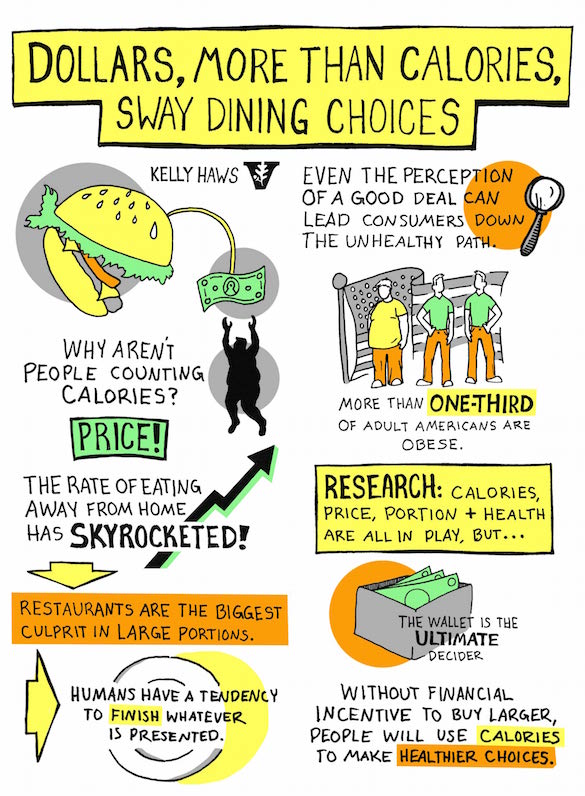

Despite a mandate from the Affordable Care Act that restaurants with 20 or more locations post calories on their menus, people don’t seem to be choosing healthier dishes. New work from Vanderbilt University suggests there’s another number that may play a critical role in dining decisions: price.

In America’s continuing fight against obesity, posting calories on menus⎯so consumers can know what dishes are the healthier choices⎯seemed a promising strategy to give diners the upper hand in the battle of the bulge. But in the real world, cost matters. When diners are presented with a good value on an unhealthy meal, they take it.

“When people are at restaurants making decisions, they don’t ignore price,” said Kelly Haws, an associate professor of marketing at the Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management.

The study is being published in the February 2016 issue of the journal Appetite. Peggy Liu, a Ph.D. candidate in marketing at the Fuqua School of Business at Duke University, was a co-author on the study.

Understanding how people make decisions about what they eat has compelling public health implications. Numbers from the Journal of the American Medical Association show that as of 2012, more than one third of adults were obese. Obesity brings a host of serious health problems, some of which are among the leading causes of preventable deaths in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Research also shows that Americans are getting an increasing share of their calories from restaurants.

“The rate of eating away from home has skyrocketed in the last couple of decades,” said Haws, adding, “[rquote]Restaurants are the biggest culprit in large portion sizes.”[/rquote]

In addition, researchers have found that humans have a tendency to finish whatever is presented to us as a “portion”⎯even if it contains far more calories than we need in single meal. Some restaurants offer meals labeled as a single serving that contain more than 2,200 calories. The U.S. Department of Agriculture recommends a daily caloric intake of 2,000-2,200 calories for a moderately active, 19- to 30-year-old female.

In her study, Haws examined what happened when diners could choose between a full order and a half order of an entrée. It’s a choice that reflects what many restaurants have begun to offer.

The authors divided 245 participants into four groups, and asked them to order dinner from four different versions of a dinner menu. All groups were offered the same tasty-sounding dishes. Half the entrées were a healthier option; the other half not so healthy⎯for example, grilled fish tacos (a lighter dish) and fish and chips (everything fried). Each entrée was offered as a half order or a full order.

On all the menus, full orders were exactly the same price. The key difference was in how the half orders were priced. Half of the menus used what is called linear pricing⎯the price of a half order was approximately half the price of a full order. A full order of those fish tacos would set you back $9.99, the half order, $4.99.

On all the menus, full orders were exactly the same price. The key difference was in how the half orders were priced. Half of the menus used what is called linear pricing⎯the price of a half order was approximately half the price of a full order. A full order of those fish tacos would set you back $9.99, the half order, $4.99.

The other menus used non-linear pricing, which is more common in restaurants⎯a half order was only approximately 20 percent cheaper than a full order. A full order of fish tacos still cost $9.99, but the half order was priced at $7.99; in terms of price per unit, the full order was a much better deal than the half order.

Of these menus, one had calorie information and linear pricing, one had no calorie information and linear pricing, one had calorie information and non-linear pricing, and one had no calorie information and non-linear pricing. So there were four variables in play: calories ordered, price paid, portion size of entrée (full or half), and healthiness of entrée (healthy or unhealthy).

So what happened when the dinner orders came in? The results suggest that when it comes to food choices, the wallet is the ultimate enabler.

When the half order was only 20 percent cheaper than the full order⎯regardless of whether calorie information was available⎯people went for full orders of the unhealthier menu choices (the fish and chips, instead of the fish tacos). It appears that the lure of a discount on the larger portion allowed diners to justify going for the unhealthy dinner.

“When the value is bigger, it gives people the edge to order larger portions,” Haws said. “So if you offer people a good deal, the calorie information is kind of irrelevant.”

However, something interesting happened with linear pricing⎯when a full order wasn’t a better “deal” than a half order. Diners still chose full orders, but, when armed with calorie information, they went for healthier options (the fish tacos instead of the fish and chips).

“[rquote]When the financial incentive to purchase the larger size was removed, then the calorie information did seem to play a positive role[/rquote],” Haws said.

In other words, diners couldn’t easily justify going for the “everything fried” option, since it didn’t seem like a deal.

Even though the price people paid didn’t change, their perception of value changed, and health played a role in their decision.

“The bottom line is that without a financial incentive for buying larger, people use the calorie information to make healthier choices,” Haws said.

Kelly Haws, et al,. “Half-size me? How calorie and price information influence ordering on restaurant menus with both half and full entree portion sizes.” (Appetite, 2016)

By Brett Israel