While it’s no surprise that a lot of musicians live and work in Music City, it is unusual how tight-knit and collegial the music community is.

To better understand what—and who—underpins a successful artistic peer community, Dan Cornfield, professor of sociology, conducted more than 75 interviews with Nashville music professionals from across the industry.

His findings appear in his new book, Beyond the Beat: Musicians Building Community in Nashville, published by Princeton University Press.

An ethos of ‘indie mutualism’

A rising share of Nashville’s musicians are independent artists, a trend Cornfield links to the boom in Nashville’s demographic diversity—and diversity awareness—over the past 30 years. Since 1980, Nashville has seen a considerable rise in immigration, as well as increased visibility of women, people of color and members of the LGBT community. Additionally, Nashville became a destination city for musicians around the

United States. As a result, Nashville’s music scene has blossomed to include not just country, but also rock, gospel, Latin jazz, hip-hop and Americana, among other genres.

These musicians, Cornfield says, have created an “exemplary peer community” grounded in a culture of generous cross-promotion, mentoring and collaboration. They are exceptionally active

supporters of each others’ work, whether by driving attendance to each others’ shows, playing on and producing each others’ albums or striving to give local up-and-comers the chance to share stages, tours and even airtime with established artists.

These efforts, led by individuals Cornfield calls artist-activists, help independent artists minimize the risks of musical entrepreneurship by providing access to career services and support that major labels typically provide, Cornfield says. “You could call it a community founded on an ethos of ‘indie mutualism.’”

The making of an artist-activist

Cornfield examined the factors that lead musicians to become artist-activists. He found that artist-activists are more likely to be motivated by the promise of artistic freedom than by fame or fortune, and that the audience they value most is their peers, more than consumers or even themselves. Professional musicians inspired by the rebellious musical movements of their adolescence are more likely to inhabit artistic roles in their musical community, while those inspired by the music in their homes are more likely to play supportive roles

Cornfield examined the factors that lead musicians to become artist-activists. He found that artist-activists are more likely to be motivated by the promise of artistic freedom than by fame or fortune, and that the audience they value most is their peers, more than consumers or even themselves. Professional musicians inspired by the rebellious musical movements of their adolescence are more likely to inhabit artistic roles in their musical community, while those inspired by the music in their homes are more likely to play supportive roles

In addition to identifying which artist-activists tend to seek the spotlight and which prefer to work behind the scenes, Cornfield has identified three general roles that artist-activists play in a successful musical community: the artist-producer, the social entrepreneur and the artist advocate. While people may play more than one role, Cornfield has found that they gravitate toward roles that mitigate what they perceive to be the greatest threats to a musical career—what Cornfield calls a risk orientation.

The artist-producer not only performs his or her own work, but also produces and promotes the work of others. According to Cornfield’s analysis, artist-producers tend to have a personal risk orientation, believing the greatest barrier to becoming a working musician is one’s own artistic and career choices.

The social entrepreneur makes business decisions that benefit local musicians, like hosting songwriters’ nights or starting a record label. Cornfield finds social entrepreneurs tend to have an interpersonal risk orientation, and are motivated to break down social barriers that prevent musicians from building an audience, like nepotism, racism and cronyism.

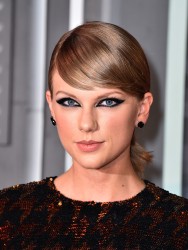

The artist advocate works to influence policies, economic conditions or industry practices that affect musicians, for example, as an artistic trade unionist. Artist-advocates tend to view these broader structural impediments as the greatest threat to a musical career, what Cornfield calls an impersonal risk orientation.

The artist advocate works to influence policies, economic conditions or industry practices that affect musicians, for example, as an artistic trade unionist. Artist-advocates tend to view these broader structural impediments as the greatest threat to a musical career, what Cornfield calls an impersonal risk orientation.

These three roles function in concert to create a community of mutual support and protection for the independent artist.

Beyond Nashville

Whether the kind of community that has developed in Nashville can be replicated in other cities remains to be seen.

Nashville is a bit of a rare bird because it has a depth of recording infrastructure that few other American cities share, making it unlikely that music communities like Nashville’s could arise just anywhere. But Cornfield thinks the Nashville-type model could certainly be generalized to the other arts.

Cornfield believes a Nashville-type arts community would most likely emerge in a city that, like Nashville:

- Both produces and consumes significant amounts of art

- Has a critical mass of artists

- Enjoys a robust local economy

- Has sufficient organizational and political resources to support arts activists

These community features, Cornfield says, are most likely to encourage the growth of a community that supports individual expression, creative professional development and economic well-being for artists and the artistic professions.