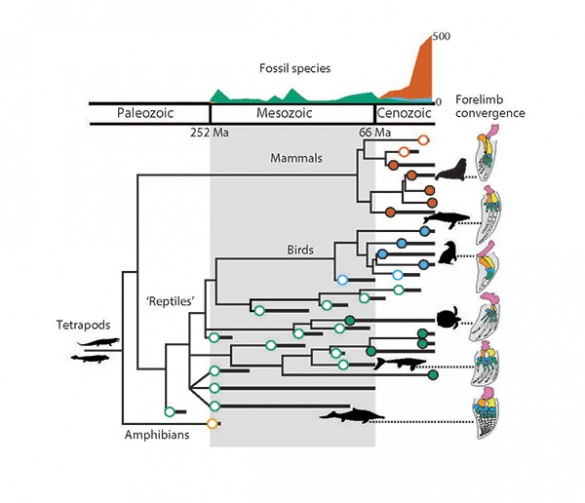

Whales, dolphins, seals and sea turtles are members of an exceptional group of animals, called marine tetrapods, that have moved from the sea to the land and back to the sea again over the last 350 million years — each time making radical changes to their life style, body shape, physiology and sensory systems.

“These land-to-sea transitions act like repeated evolutionary experiments,” said Neil Kelley, a former lecturer in earth and environmental sciences at Vanderbilt University and a post-doctoral researcher at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s department of paleobiology. “[rquote]We can learn quite a bit about evolution by comparing the similarities and differences in each group.”[/rquote]

Kelley is the lead author of a new scientific review performed by scientists at the Smithsonian who have synthesized decades of scientific findings regarding the changes that these land species underwent in order to thrive in the marine environment. He began the research while at Vanderbilt and finished it up at the Smithsonian. The study results are published in the Apr. 17 issue of the journal Science.

Marine tetrapods represent a diverse group of living and extinct species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians and birds that all play, or have played, a critical role as large ocean predators in marine ecosystems past and present.

The reverse migration of land animals back to the ocean began 250 million years ago, following the Great Permian Extinction, colloquially known as the Great Dying because it was the most severe mass extinction event known, with 96 percent of all marine species and 70 percent of land animals going extinct. It took the Earth’s ecosystems up to 10 million years to recover.

“We know from the fossil record that previous times of profound change in the oceans were important turning points in the evolutionary history of marine species,” said Kelley. “Today’s oceans continue to change, largely from human activities. This paper provides the evolutionary context for understanding how living species of marine predators will evolve and adapt to these changes.”

According to the paleobiologist, there is even evidence that some species may have been double dippers: They have transitioned between sea and land more than once.

“Snakes are one example that comes to mind,” said Kelley. “There is evidence that they went through an early marine phase, when they still had legs. Since then different groups of snakes have repeatedly gone back into the ocean. So it may be that snakes are particularly prone to habitat switching.”

Another possible example is the elephant, which scientists know is closely related to manatees and sea cows. “Some evidence suggests that early elephants were highly aquatic – but whether they ever ventured into the ocean or stuck to freshwater is unknown,” he said.

For more information, check out the Smithsonian news release:

Smithsonian Scientists Show How Repeated Marine Predator Evolution Tracks Changes in Ancient and Anthropocene Oceans

the paper in the journal Science:

Evolutionary innovation and ecology in marine tetrapods from the Triassic to the Anthropocene

or Kelley’s interview on NPR’s The Splendid Table:

How land animals became marine animals: ‘They followed their stomachs’