New research finds that no matter where you earn your graduate degree, the prestige of your undergraduate institution continues to affect earnings. In fact, college graduates who earn their undergraduate degree from a less prestigious university and a graduate degree from an elite university earn much less than those who attend both an elite undergraduate and graduate school. And it is unlikely their salary will ever catch up.

“Status of the graduate degree-granting institution should have a more important relation to earnings than status of the undergraduate institution,” said Joni Hersch, professor of law and economics at Vanderbilt Law School. “[But] even high ability students who attend nonselective institutions for their bachelor’s degrees are, on average, unable to overcome their initial placement by moving up to an elite graduate or professional school for an advanced degree.”

Hersch is author of, “Catching Up Is Hard to Do: Undergraduate Prestige, Elite Graduate Programs, and the Earnings Premium.”

Hersch used data from the 2003 and 2010 National Survey of College Graduates, which provides information on a representative sample of almost 178,000 college graduates, including more than 83,000 students earning graduate degrees.

Hersch compared the Carnegie Classifications to selectivity categories from Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges to divide schools into categories. Hersch also used various classifications with assistance from the and to divide schools into categories. Roughly speaking, Tier 1 schools are top private research institutions. Tier 2 schools are selective private liberal arts colleges. Tier 3 are top public research universities and Tier 4 are remaining four-year universities and colleges. Because ability influences whether a student is accepted to a selective institution, Hersch accounted for ability in her study by examining graduates of similarly selective graduate programs.

Elite earnings

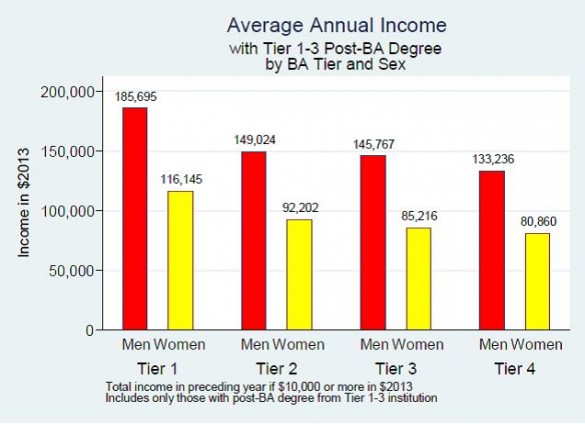

Hersch’s research found that graduates of Tier 1 schools earn a lot more than everyone else.

But even when looking at those with graduate degrees from elite schools, the students who went to a lower tier undergraduate school earn considerably less.

“Earning an elite graduate degree does little to reduce the pay gap associated with an elite undergraduate degree,” writes Hersch.

Among those who earned a graduate degree from Tier 1 – Tier 3 institutions, men from Tier 1 undergraduate schools earn 39 percent more than men with undergraduate degrees from Tier 4 schools. Among women with top graduate degrees, those from Tier 1 undergraduate schools earn 44 percent more than women with undergraduate degrees from Tier 4 schools.

Moving up to graduate school

Hersch finds that where a student earns his or her bachelor’s degree is closely related to whether that student even goes to graduate school.

Among Tier 4 graduates, the highest degree is a bachelor’s degree for 69 percent of men and 68 percent of women. In contrast, more than 50 percent of men from Tier 1 and Tier 2 schools and almost half of women from Tiers 1 and 2 schools will earn a graduate degree.

And of the small percentage of students from lower tier institutions who earn a graduate degree, a tiny number move up to a top tier graduate school.

“The odds of a Tier 4 student having a graduate degree from a Tier 1 institution are quite small with 3 percent among men and 2 percent among women,” writes Hersch.

Medical and legal

The type of graduate degree a student earns is also strongly related to prestige of the undergraduate institution. Hersch finds that among male Tier 1 graduates, nearly 9 percent have medical degrees and nearly 11 percent have law degrees. In contrast, among male Tier 4 graduates, fewer than 2 percent have medical degrees and fewer than 3 percent have law degrees.

Among female Tier 1 graduates, 5 percent have medical degrees and nearly 8 percent have law degrees. But less than 1 percent of female Tier 4 graduates have medical degrees and only slightly more than 1 percent have law degrees.

Tier levels

To identify schools considered elite and to put these schools into tier levels, Hersch used both the Carnegie classification and the Barron’s Profiles of American Colleges. The Barron’s Profiles look at quality indicators of each year’s entering class (SAT or ACT, high school GPA and high school class rank, and percent of applicants accepted). Barron’s then places colleges into seven categories: most competitive, highly competitive, very competitive, competitive, less competitive, noncompetitive, and special.

The Carnegie classifications are based on factors such as the highest degree awarded; the number, type, and field diversity of post-baccalaureate degrees awarded annually; and federal research support. For example, Research I universities offer a full range of baccalaureate programs through the doctorate, give high priority to research, award fifty or more doctoral degrees each year, and receive annually $40 million or more in federal support.