It’s been 20 years since Project PAVE, a Tennessee program providing low-vision evaluations for children, was launched.

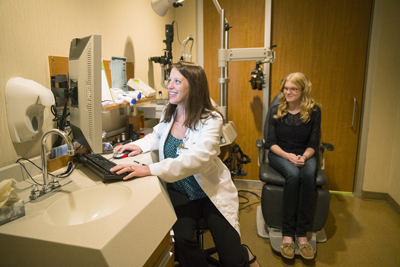

Lori Ann Kehler O.D., the newly appointed principal investigator of Project PAVE (Providing Access to the Visual Environment), is eager to see the impact that one of the nation’s leading programs assisting low-vision patients will have in the coming years.

Nearly 1,200 patients have been helped at the clinic, which also prescribes optical devices, instruction and follow-up as well as technical assistance for eligible youths ages 3-21 in Tennessee. Low-vision impairment is a reduction in vision due to ocular or neurological disease, not correctable with glasses, surgery or contact lenses. Low vision is eyesight in the range of 20/50 or worse in the better-seeing eye.

Since stepping into the role in January, Kehler has made a few changes in hopes of improving outcomes.

“We are now working closer with the child’s primary eye doctor to better understand the child’s progress and prognosis in an effort to complement their medical treatment plan,” Kehler said.

“The team approach allows us to marry the educational recommendations with the medical needs of each patient.

“We plan to publish outcome data on the use of optical devices and the academic success of our patients. I am hopeful that the data can be used as a model for other programs around the country as well to demonstrate the need for insurers to cover low-vision devices.”

Kehler said PAVE is special because it is the only feasible way for many of the children to obtain their low-vision devices, a key component in their continued education and future independence.

Two college-bound students from this year’s clinic will be able to live independently on their respective college campuses in part because of the devices prescribed and provided by PAVE, she said.

The majority of students from across the state are seen at the Tennessee Lions Eye Center for Children at the Vanderbilt Eye Institute between April and November.

About 20 percent of patients are evaluated by a low-vision specialist in Knoxville, Bruce Gilliland, O.D., to reduce the need to travel to VEI.

Since 1994, the Tennessee Department of Education has funded Project PAVE via a nearly $1 million grant thanks to the work of Anne Corn, Ed.D., professor of Special Education and Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, who started the program.

“I think it is terribly exciting that the program is still in operation,” Corn said. “PAVE has really laid the foundation. There is much more available today for low-vision patients and PAVE was a big part of increasing awareness of the need for such programs. It has had an effective impact on functional vision.”

The program operates with the assistance of two certified Teachers of Students with Visual Impairments, Judy Alford in East Tennessee and Brandi McRedmond at VEI. McRedmond serves as coordinator of Project PAVE and both ensure that school teachers as well as patient families are instructed on the use of the low-vision devices provided to students.