When something attacks you, you want to attack it back.

That’s how Lillian “Tooty” Bradford views her late husband James “Jimmy” Bradford Jr.’s decision to make an initial gift to fund melanoma research at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (VICC). The goal: to attack cancerous melanoma with the help of some of the greatest minds and researchers at Vanderbilt’s academic medical center, using the right confluence of technological advances in the field.

Jimmy, a Nashville banking magnate, was diagnosed with advanced-stage melanoma at the end of summer 2008. In determining the best course of treatment, his care team — oncologist Jeffrey Sosman, M.D., surgeon James Netterville, M.D., and then Vanderbilt oncologist William Pao, M.D., Ph.D., — tested his cancer tissue for the most common melanoma-associated mutations in genes called BRAF and KIT, which respond well to targeted therapies. His tumor was negative for these mutations. Instead, he had a different mutation, later identified as BRAF L597, which left only standard chemotherapy for treatment.

As was characteristic of Jimmy, he was thinking of others while battling his own cancer. He wanted doctors to use his tumor to find out how they could help future melanoma patients with a similar mutation. The Bradfords even made two gifts for a discovery grant to make the research possible. He died a little more than a year after his diagnosis.

The seeds he planted have grown and flourished into discoveries and a promising new therapy for other melanoma patients, beyond what was imagined at the time.

“When (Jimmy’s medical team) sat down, we thought, ‘what can we do with this money that will be meaningful both to him and to cancer treatment,’ said Sosman, professor of Medicine in Hematology/Oncology and director of the Melanoma and Tumor Immunotherapy Program. “I don’t think we imagined it would lead ultimately to a clinical trial and impact a whole set of other patients, but we knew we would learn something important,” he said.

The Bradfords’ gift would be used to examine the DNA of his tumor and look for mutations using whole genome sequencing, a time-intensive and costly process. Once they had the analysis, which took six months, and knew his tumor’s mutations, they could see if any emerging or existing therapies already in the pipeline could be an effective treatment. It just so happened that there was.

“When we looked, it seemed to be sensitive to a class of drugs — called MEK inhibitors — which were being investigated in a clinical trial,” said Sosman, Ingram Professor of Cancer Research.

“At the same time, we had a patient with a similar mutation who was being treated in a trial with an experimental MEK inhibitor and he had a positive response.”

“If Mr. Bradford came to us today, we would know this information and we would probably put him on one of these drugs. This has been a major sea change in the way we approach melanoma. We have real drugs that do work. At the time for him (just six years ago), chemotherapy was the only option,” Sosman continued.

Because of what researchers learned from Bradford’s tumor, made possible by his gift, doctors at Vanderbilt modified the mutation testing panel, so future patients with L597 could be identified. They are also conducting clinical trials.

“They sort of hit a home run,” Tooty Bradford said.

The Vanderbilt researchers published their findings on Jimmy’s mutation and the identification of a promising new therapy in the September 2012 issue of the journal Cancer Discovery. The article was featured on the front cover with an artistic representation of the genetic sequence of Jimmy’s tumor.

Vanderbilt co-authors, in addition to Sosman, Pao and Netterville, included: Kimberly Brown Dahlman, Ph.D., Zhongming Zhao, Ph.D., Cindy Vnencak-Jones, Ph.D., Donald Hucks, M.S., Donna Hicks, B.S., Pamela Lyle, M.D., Zengliu Su, M.D., Ph.D., Peilin Jia, Ph.D., Katherine Hutchinson, B.S., and Junfeng Xia, Ph.D.

Tooty said she and her family wanted to keep the hope for other patients going after Jimmy died in March 2010, and Vanderbilt’s unique position as a medical and academic powerhouse would make that possible.

Vanderbilt is one of only a few academic medical centers in the United States located on the same campus with leading scientists who are finding new treatments to be brought to the patient’s bedside. An investment in medical research at Vanderbilt is an investment in the future of medicine by providing support for the individuals who devote their lives to innovating by improving the quality and accessibility of therapies.

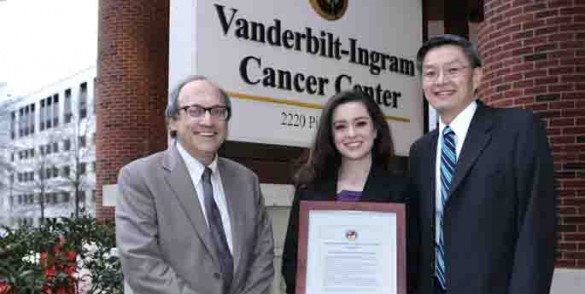

Tooty, a Vanderbilt alumna, made another gift in December 2010 in honor of the care Jimmy and her family received at VICC. With the help of Tooty, family, friends and the community, the James C. Bradford Jr. Endowed Fund in Melanoma Research was established in 2011 to serve as a continuous and permanent source of support for Vanderbilt researchers studying this type of cancer. To date, nearly $1 million has been pledged for the fund. The goal is to secure $2 million.

“Jimmy would be so touched by the people who have responded,” Tooty said. “He was such a sweet man. He had a smile for everybody. He was a good, kind person. He made us, as a family, think about going further (to support this research).”

Science has come a long way in the past few years since Jimmy’s tumor was first sequenced. Whole genome sequencing can now be compressed into a few weeks. Discovery grants and endowments like the Bradfords’ can be used to push the envelope even further and to capitalize on the potential for other novel therapies.

“When people give a Discovery Grant, it can be used to decipher a fundamental cellular mechanism that plays a role in the formation of cancer and/or treatment of the disease,” said Jennifer Pietenpol, Ph.D., director of VICC, the B.F. Byrd Jr. Professor of Molecular Oncology and professor of Biochemistry, Cancer Biology and Otolaryngology.

“This knowledge is critical for the future design of approaches to prevent and treat cancers. Alternatively, a Discovery Grant can be used to comprehensively sequence tumors from patients that either don’t respond to therapy or have an exceptional response. Knowledge of the mutations in a patient’s tumor that has either response is extremely valuable and critical for the design of new therapies and clinical trials. Further, in some cases the information can be translated to the clinical very quickly as an “actionable” mutation to which therapy can be aligned.”

The Bradford Discovery Grant is a prime example of the possibilities.

“Mr. Bradford’s vision to help others was realized in the Discovery Grant and was made possible, in part, due to the level of funding and also the timing of the grant relative to where we were with the molecular genetics and the technology of whole genome sequencing,” Pietenpol said.

“One would argue it was a most impactful gift from the standpoint of a discovery having immediate translation to patients. It did exactly what Jimmy wanted,” Pietenpol added.