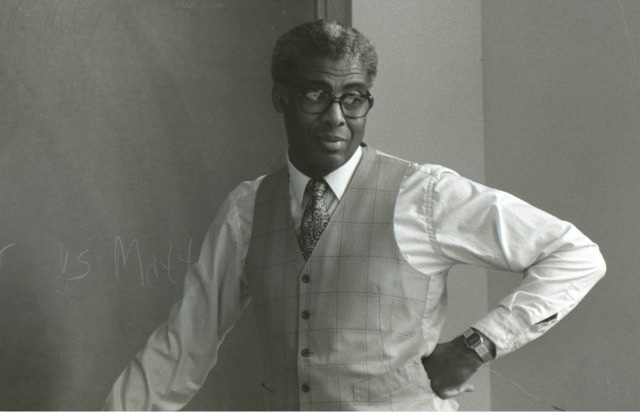

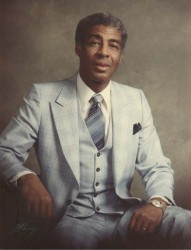

One of Vanderbilt’s newest residence halls has been named for a pioneering Nashville civil rights leader who also was the university’s first African American administrator. Smith Hall, located in Moore College on the main campus, pays tribute to the late Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, who served as assistant dean of Vanderbilt Divinity School from 1969 until his death in 1984.

“Kelly was one of the premiere prophetic voices as it relates to justice and freedom for African American people,” said Forrest Harris, director of Vanderbilt’s Kelly Miller Smith Institute on Black Church Studies.

Harris, who is also an associate professor of the practice of ministry, said Smith had a strong influence on his own decision to enroll at Vanderbilt Divinity School in the 1980s. “Kelly was a superb scholar, teacher and preacher par excellence,” Harris said. “His impact on my thinking and understanding of leadership was exponential.”

“Kelly was committed to nonviolent work, through love, truth and treating people with dignity,” said the Rev. James Lawson Jr., who has played key roles in the civil rights movement and Vanderbilt’s history. “Kelly was one of those individuals who felt that you cannot remove racism by imitating it. He believed that the work of desegregation was a part of the ministry of church.”

Smith was born in the all-black town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi. “Kelly had grown up in the struggle (for racial equality), and once you grow up in a struggle, there is no way to divorce yourself from it,” said Lewis V. Baldwin, professor of religious studies, emeritus, at Vanderbilt. Baldwin first met Smith when Baldwin was a student at Crowe’s Seminary.

Smith attended Tennessee State University for two years before transferring to Morehouse College, where he received a bachelor of arts degree. He then earned a bachelor of divinity degree (current equivalent would be master’s) from Howard University.

Smith was pastor of a Baptist church in Vicksburg, Mississippi, and chair of the Department of Religion at Natchez College before returning to Nashville in 1951 to serve First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill. Smith, whom Ebony magazine named “One of America’s 10 Most Outstanding Preachers,” was heavily involved in the push for civil rights even before the sit-ins at downtown Nashville lunch counters.

In 1954, while Smith was serving as president of the Nashville chapter of the NAACP, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against segregation in public schools. Smith joined 12 other black parents in filing suit against the Nashville Board of Education. Four years later, Smith founded the Nashville Christian Leadership Council, an affiliate of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, led by Martin Luther King Jr.

One way Smith became connected to Vanderbilt was through professors who belonged to his church, including Old Testament scholar and former Divinity School Dean Walter Harrelson. In addition, Smith worked with Lawson, who transferred from Oberlin to Vanderbilt Divinity School in the fall of 1958. Lawson explained that Smith had invited him to serve on the Nashville Christian Leadership executive committee.

“Kelly was committed to nonviolent work, through love, truth and treating people with dignity.”

—the Rev. James Lawson Jr.

“A group of us met from January to June of 1959 to talk about what the issues were in Nashville and where we wanted to begin this direct-action campaign,” Lawson said. “That was a decision that Kelly participated in with me. You have to realize that in the late 1950s, there was almost no other black community in the Southeast that was engaged in an assessment of their own situation for the purpose of action to change it and improve it. Up to that time, no one had really thought of public desegregation.”

Smith helped organize and support the students taking part in the sit-ins that led to the integration of Nashville’s downtown lunch counters. “My father was a close friend of Dr. King, and those persons who were involved in the movement all knew each other well, so that was part of the impetus for the work being done in Nashville and why it was so effective,” said the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith Jr., who now leads First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill.

Smith Jr. said that his dad calmly juggled many responsibilities throughout his multi-faceted career. “One of his proudest achievements was a grant-funded program at Vanderbilt that sought to bridge persons from different academic levels,” Smith Jr. said. “Students in the classes ranged from those with only a high school diploma to individuals with advanced seminary training. They would come together, studying and experiencing the dialogue.”

As a student then at the Divinity School, Smith Jr. said that he was fortunate to participate in some of those class discussions.

“Like all black religious leaders, Smith’s ministry was characterized by many diverse functions, offices and associations,” wrote Peter J. Paris, a former Vanderbilt Divinity professor (now emeritus at Princeton Theological Seminary), in the introduction to the Kelly Miller Smith Papers, donated by Smith’s family to Vanderbilt in 1985. “But unlike many, Smith’s leadership, more often than not, produced the required results. He was able to mobilize people around issues and inspire them to become actively involved. Many did so simply because he asked them.”

“(Kelly and King) shared a vision of the beloved community, meaning a totally integrated society, and their activism was put to the service transforming the South.”

—Lewis V. Baldwin

Paris noted in his introduction to the papers that Smith is believed to have been the first person in the nation to offer a full course on the thought of Howard Thurman, a noted African American minister, author and spiritual adviser to King. The 1983 Lyman Beecher Lecture Series at Yale University was delivered by Smith and the texts were published in the book Social Crisis Preaching by Mercer University Press.

Baldwin was deeply saddened when Smith died in June 1984, just two weeks before Baldwin arrived on campus as a faculty member in Religious Studies. “I knew that he set high standards in terms of prophetic preaching and teaching at the Divinity School. He had a major influence on my decision to come to Vanderbilt.”

Smith’s correspondence with King is included in his papers. “Kelly was among 11 black leaders who were closely associated with Martin Luther King Jr.,” said Baldwin, a renowned scholar of King’s legacy. “They shared a vision of the beloved community, meaning a totally integrated society, and their activism was put to the service transforming the South and creating that kind of society. I am glad that today’s scholars have an opportunity to look back on the life of this great man and to reflect on his many roles as a preacher, civil rights activist and one who actually paved the way for President Obama.”

The Kelly Miller Smith Papers as well as the Kelly Miller Smith Institute on Black Church Studies at Vanderbilt serve as a testament to the civil rights activist’s legacy.

In addition, a recorded interview that author Robert Penn Warren conducted with Smith for the book Who Speaks for the Negro is now part of a digital archive on the Vanderbilt website.

“Intellectual activism as it relates to social justice was what distinguished Kelly at Vanderbilt and in the community,” Harris said. “After his death, Vanderbilt colleagues realized the depth of his contributions to the university as well as the nation and an institute on the black church was launched. I was so fortunate that after having had Kelly as a professor and having graduated from the Divinity School, I became the institute’s first director.”

Harris, who is also president of American Baptist College, is now marking his 26th year at the institute. A plan to strengthen the institute’s current program to include a digital archive of liberation and womanist ethics and black church theologies, as well as a research collection on non-violence philosophy, will require growth in the endowment before its launch.

Harris noted that the institute was among the first in the nation to launch national programs that involve dialogues around what it means to be black and Christian in America. “We continue to move forward in seeing the possibilities and potential of the impact that we will have in interdisciplinary work around issues of race, culture and faith.”