The ancient Aztecs are perhaps most famous for not only their practice of human sacrifice but the spectacle surrounding it. They killed prisoners of war and a chosen cohort of their own citizens elected to embody the gods for a year before meeting their doom in a public ritual—culminating in the offering of the victims’ still-beating hearts to the gods.

But, as Vanderbilt archaeologist Markus Eberl describes in the most recent issue of the Cambridge Archaeological Journal, three prehispanic Mexican codices show that the blood link between the Aztecs and their gods actually begins at birth.

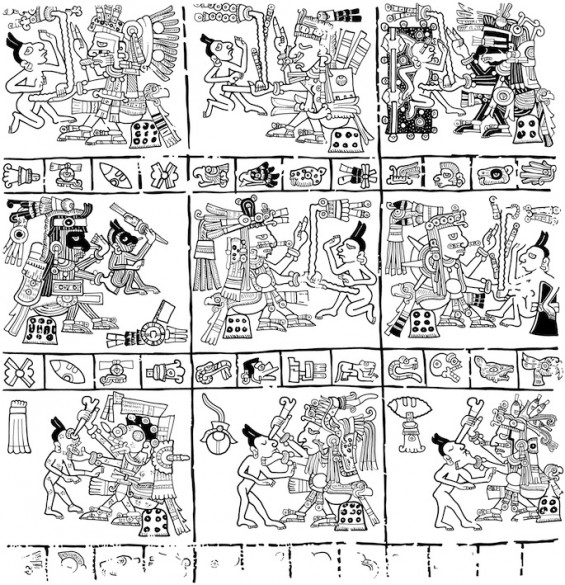

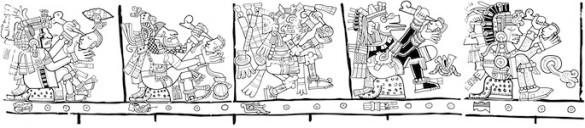

In “Nourishing Gods: Birth and Personhood in Highland Mexican Codices,” Eberl writes that the codices, or “day books,” are believed to have belonged to the Aztec peoples of the Mixteca-Puebla-Tlaxcala region of central Mexico. Painted on screenfolded pieces of hide, the codices contain stories about the gods, Aztec ideology and various almanacs that served as divinatory manuals for Aztec soothsayers.

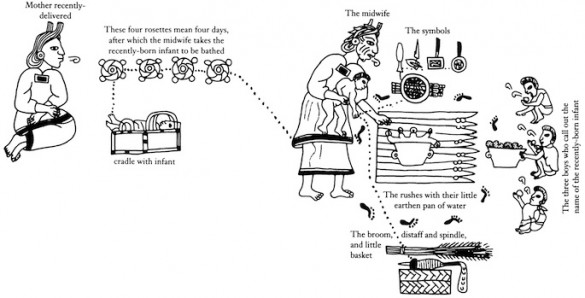

When an Aztec child was born, the soothsayers would consult the birth almanacs contained in these codices to determine the most auspicious date to initiate the child into the Aztec community.

The newborn would then undergo a series of carefully choreographed birth rituals designed to imbue the child with a soul, determine the child’s destiny, and establish the link between child and gods. These birth rituals included bathing and naming the child, passing the child over a fire, reading the child’s horoscope, presenting the child to the gods and, among some communities, drawing a bit of the child’s blood.

These rituals were first recorded for posterity by Spanish witnesses, who interpreted them through a European Christian lens, but it is not well understood what they meant to the Aztecs themselves. The codices, Eberl says, provide that important insight.

“Among the Aztecs in highland Mexico, personhood rests on the possession of a destiny,” Eberl writes. The divinatory information contained within the codices was the key to an Aztec infant’s transformation from mere flesh and bones to a full person.

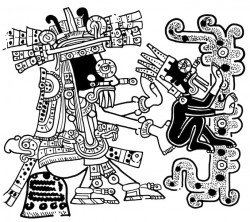

The almanacs depict four versions of a 20-day ritual cycle—each version depicting a god or goddess performing one of four tasks: piercing the child, lifting the child, handling the umbilical cord or nursing the child. Each version was also subdivided into groups of four days each, each group associated with a particular symbol or quality. The soothsayers would consider the significance of each god or goddess, activity and symbol associated with the chosen day to determine the child’s destiny.

The four tasks performed by the deities in the codices—piercing, lifting, handling the umbilical cord and nursing—represented the four ways the gods influenced the child’s destiny.

- Piercing the child:Though few were chosen to sacrifice their lives, all Aztecs werecalled upon to sacrifice their blood. Pain and suffering were viewed as transformative. Often the codices depict the god or goddess piercing an eyeball, signifying the child’s transformation into a being that could see clearly—literally and figuratively. Clear vision symbolized the ability to learn and discern truth. Other panels depict piercing of the mouth or body.

- Presenting the child: A child didn’t just need to be able to see, but also needed to be seen by the community of gods in order to be recognized as a being under divine protection. The god or goddess raises the child up to symbolize that recognition.

- Handling the umbilical cord: By handling the umbilical cord, the god or goddess is asserting a link between the child and the divine. As the unborn child was linked to its mother, so the newborn is linked to its patron god or goddess.

- Nursing the child: Although the Aztecs are expected to make sacrifices to their gods, they can also expect to receive nourishment from them. Panels displaying female deities nursing children symbolize that reciprocal relationship.

This reciprocal relationship, or covenant, was called tlatlatlaqualiliztli, or “the nourishment of the gods with the blood of sacrifice.” In its most extreme interpretation, the covenant culminated in human sacrifice. “Those adults who were selected to impersonate the gods died voluntarily,” Eberl said. “By nourishing the gods with their blood, they returned the gift of life that the gods had bestowed on them at birth.”