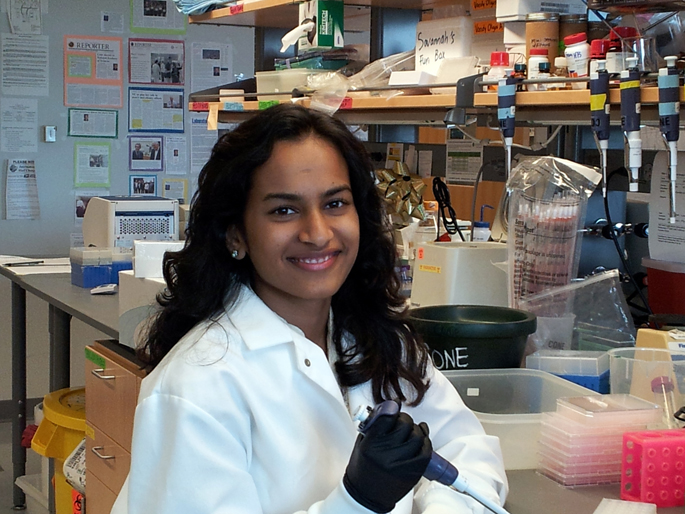

A California high school student helped accelerate an anti-obesity drug discovery program at Vanderbilt University this summer — and provided the proof-of-principle for a new technique that could save the lab an estimated $250,000 in the process.

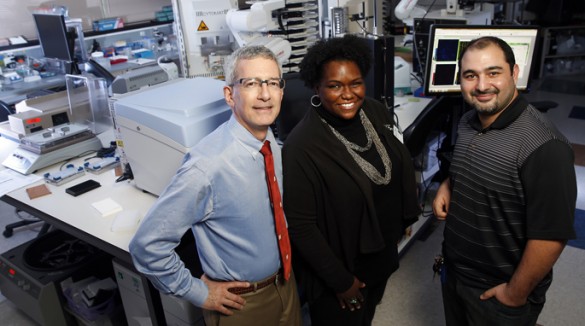

Assigned to the lab of Roger Cone, Ph.D., who chairs the Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics, Aloukika Shah implemented an in-house strategy for testing 56 compounds for specific drug-like activity. An outside firm would have charged up to $5,000 per compound to do the work.

“In a very real sense, Ms. Shah’s work generated results that could have cost as much as $250,000, if contracted out,” Cone said. “Further, her work validated a new approach to specificity testing in early stage drug discovery.”

Cone and his colleagues are searching for compounds that can “tune-up” the activity of the melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R). Previously they discovered that nerves in the brain expressing this receptor play an important role in regulating feeding behavior and fat metabolism.

Defective MC4R signaling is now known to be the most common cause of severe childhood obesity. A drug that overcomes this genetic deficit theoretically could prevent or reverse this condition, Cone said.

This summer Cone’s research assistant, Savannah Williams, and postdoctoral fellow Julien Sebag, Ph.D., mentored Shah, 17, a rising senior at Kimball High School in Tracy, Calif., during a six-week-long Research Experience for High School Students (REHSS) program.

Shah’s story illustrates the importance of investing in science education, said program coordinator Kimberly Mulligan, Ph.D. Of the 200 students who have participated in REHSS since

it was established in 2006, the majority have pursued college studies in science, technology, engineering or mathematics, she said.

Shah said she applied for the program because she wanted to have a university-based laboratory experience. Her love of science, she said, was stimulated by her parents’ unflagging interest in learning new things, and by seeing how advances in medicine helped her late grandfather, who had diabetes.

When she arrived at Vanderbilt in early June, Shah was matched with the Cone lab and assigned to the MC4R drug discovery project.

The research is supported by a grant (5R01DK070332) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Previous attempts to directly activate MC4R activity have been stymied by an unwanted rise in blood pressure in some people. Cone and his colleagues turned to “allosteric modulators,” compounds that, by indirectly “tuning-up” receptor activity, are less likely to cause side effects.

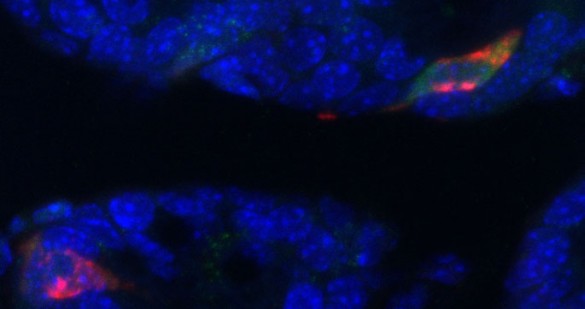

Because MC4R is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), however, the compounds could activate other GPCRs that regulate unrelated physiological functions. To test their “specificity” for MC4R, the researchers needed to gauge their effect on a range of GPCR expression in cell lines grown in the laboratory.

Until recently that work was usually done by outside firms. But last year researchers at Indiana University reported that they had identified the endogenous expression of hundreds of GPCRs in a handful of commonly used cell lines by using high-throughput and microarray methods.

“Light bulbs went off,” Cone said. “(We) realized we could counter-screen our compounds against a large number of receptors in a single cell line.”

At first, Shah wondered whether she’d be able to handle the complexities of laboratory science, but Cone’s research staff, graduate students and postdoctoral fellows soon put her at ease.

Under the guidance of Williams and Sebag, she quickly learned how to perform the complicated measurements of GPCR expression in cell culture.

“They were incredible,” Shah said. “They took me step-by-step through all the procedures … until I was able to do cell culturing myself and almost run the assays myself … I’m really thankful for that.” The entire experience, she added, was “just phenomenal.”

By the middle of July, she had screened all 56 drug candidates, and identified several that — because they specifically acted on MC4R — merit further development. Her results, Cone said, helped “separate the wheat from the chaff.”

Shah said she had been thinking about going to medical school, but “I believe this six-week engagement has helped to immerse me into the research world. I will consider it as another possible career option.”

“Research allows you to fulfill your curiosity,” she added. “There are not many other fields that allow such freedom.”