WATCH Vanderbilt University Museum of Art intern Brooklynn Farmer working with the Sullivan Collection prints:

By Bonnie Arant Ertelt

The old adage “what goes around comes around” is proving true in all the best ways for the newly renamed Vanderbilt University Museum of Art. Because of a provision in a gift agreement to the Brooklyn Museum of Art made by philanthropist collectors George H. Sullivan and his mother, Mary Mildred Sullivan, in the early 20th century, nearly 3,400 prints are being added to Vanderbilt’s art collection after Brooklyn removed them from their collection in 2007. As they are researched and cataloged, these new works are initiating creative teaching, learning and exhibits with departments and colleges on campus and across Nashville.

“This is such an amazing teaching collection of European prints,” says Amanda Hellman, director of the museum. “Not only do we have a range of artists, subject matter and types of prints, but there also are examples of different states or different impressions that facilitate teaching about prints, about printmaking, about the economy and the market of printmaking and how prints were used in Europe at this time-when you saw the dissemination of material differently after the printing press.

“We will exhibit them,” she says, “but more than anything, we’ll see that they serve classes well. They’ll serve student projects and internship projects, both in thinking about the conservation of the work, but also in content-driven information, research and digital exhibitions.”

Now that the gallery is officially the Vanderbilt University Museum of Art, it is working to complete its accreditation process for the American Alliance of Museums. Doing research on the works in the collection is necessary so that it can be shared with everyone who may view it or use it for teaching or research.

“It’s very rare that a curator gets to do this kind of investigative work on a scale that makes such an impact,” Hellman says. “What we find will go into our database, which will be searchable by the public.”

Courtney Wilder, BA’03, who earned her Ph.D. at the University of Michigan, was hired as a full-time curator in 2023 to catalog the additional Sullivan prints. The Brooklyn prints that arrived in 2007 number around 3,390, bringing the total, including those originally given to Peabody, to around 6,500 prints that were owned by the Sullivans.

“In addition to loose prints, the collection also includes large sheets of blue paper with prints affixed to them; the sheets appear to have been taken out of an album,” Wilder says. “It’s a very rare thing to have that, and it gives insight into how prints were collected in the early 20th century. There’s often very little rhyme or reason to how they’re organized, but other times there is. It will be an amazing tool to show students the tactility of what it meant to own prints.”

The prints are primarily etchings and engravings, ranging from the 16th century through the 19th century; the earliest is from 1532. They are printed on a variety of materials-European and Asian papers and some on silk-and there are several works by women artists, including Renaissance engraver Diana Scultori. (Thirteen of Scultori’s works are on exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

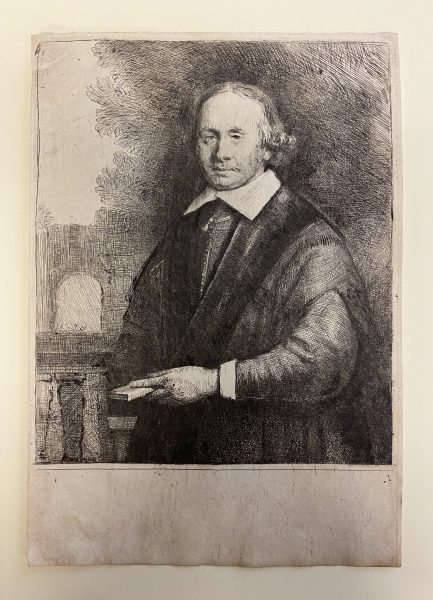

George H. Sullivan seems to have liked to collect portraits. The collection includes a technologically innovative portrait of Thomas Jefferson and an unsigned Rembrandt print dated 1665 depicting physician Jan Antonides van der Linden. The van der Linden portrait, versions of which are held by the National Gallery of Art and several other museums, is interesting for a number of reasons: It is the last print known to be made by Rembrandt, it was done as an illustration for a book after a posthumous portrait by another artist, and the resulting print was not used in the book.

“It’s interesting in terms of how the art market worked,” Wilder says, “in how [Rembrandt] was taking commissions, the kinds of jobs even great artists found themselves doing when they were in hard straits.”

The Rembrandt print is also an enigma in terms of how and when it was printed. While it seems to have been printed from the original plate, that plate was retouched posthumously, and this particular impression shows a small, looped fiber on the right shoulder of the subject. Wilder has not seen this in other impressions, but notes that the plate would be reinked for each impression. “It shows that a print is always a unique object, despite being a multiple.”

While investigating the various marks for provenance on the print, Wilder found that Sullivan seems to have bought many of his prints from the same unidentified dealer-frequently for $10 or less. The Rembrandt print appears to have been bought for $2, equivalent to around $65 today.

“Maybe the seemingly low price is due to the errant fiber or because this is a posthumous print with drypoint additions,” she says. “Or maybe the dealer didn’t realize it was a Rembrandt. But it does offer a fascinating peek into the ways the market for old master prints tends to produce rather complex objects.”

Already the collection is being used by classes in the College of Arts and Science, and not just art and art history classes. In the best tradition of the education philosopher John Dewey-interacting with the world to understand new concepts and ideas-classes in the Department of English and Department of Classical and Mediterranean Studies have used the prints to teach history, mythology, creative writing and the intersection of literature with the visual arts.

Chiara Sulprizio, senior lecturer in classical and Mediterranean studies, taught The Greek Myths during the spring semester. She brought her class to the museum as part of a “monthly encounter” assignment in which the students write about a reference to mythology they may find outside of class. They looked at prints that depicted myths they’d studied-including Apollo and Daphne, Aphrodite and Adonis, and Odysseus and the Sirens-and compared the visual representations with the original written versions from antiquity. “It was enriching to learn in a hands-on way about how the myths continued to resonate for later artists and audiences, sometimes in ways that were very different from their original ancient contexts,” Sulprizio says.

Students of graduate teaching assistant Grace LaFrentz, who studied Ovid’s Metamorphoses in a section of the English department’s Literature and Analytical Thinking class, viewed the prints on screen then went to the museum to look at them in person. Afterward, each student responded to individual prints by writing poetry, short fiction or critical reflections. “It made a big difference to be able to come into the gallery, look at the scale of these prints, closely observe and discuss their key details, and learn more about the process of printmaking from the curators,” LaFrentz says.

With the additional prints, the Vanderbilt University Museum of Art collection numbers around 11,000 works of art, making it not just a resource for campus, but also the largest collection of art in Nashville and possibly Middle Tennessee.

“This is a new era for the museum,” Hellman says. “We are trying to grow in a meaningful way, but we’re also trying to make sure that our activities are aligned with best practices. We need to understand exactly what we have, but already we know that this significant addition will serve our mission in a really beautiful way.”

A brief history of the Sullivan Collection

When George Peabody College for Teachers moved in 1911 to its current location across 21st Avenue South, education philosopher John Dewey’s experience-based learning model was prominent in its mission to prepare teachers for the South’s struggling schools. This mission attracted some influential donors, among them George H. Sullivan and his mother, Mary-son and wife of noted New York philanthropist Algernon Sydney Sullivan. The Sullivans donated fine art, prints and decorative art to Peabody from 1917 to the 1950s to be used in a comprehensive art education curriculum. Former professor and art department chair George Dutch, who was at Peabody from 1919 to 1956 and later added World War I posters and ephemera to Peabody’s art collection, wrote to Sullivan in 1923, saying, “The donations … have practically constituted the foundation of the initial gifts to the Peabody College Art Collection.” Dutch used the collection for teaching classes and organized rotating displays consistent with the Dewey philosophy of education.

In earlier years, the Sullivans had given prints to the Brooklyn Museum of Art and the New York Public Library. Their gift to the BMA carried a stipulation: Should their prints ever be removed from the Brooklyn collection, they should go to Peabody, which was at that time an independent teacher’s college. Peabody’s art collection, including the pieces from the Sullivans, has belonged to Vanderbilt since the 1979 merger of the two institutions.

When the Brooklyn prints were deaccessioned and sent to Vanderbilt in 2007, the Fine Arts Gallery was affiliated with the Department of Art History and did not have the resources to inventory the thousands of additional works. The gallery became affiliated with the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries in 2018, and, when Amanda Hellman joined the gallery in 2022, it became an independent unit reporting to the vice provost for arts, libraries and global engagement. The Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery became the Vanderbilt University Museum of Art in spring 2024.

Upon seeing the Sullivan Collection prints in storage, Hellman realized the scope of the work to be done and recently added personnel to sift through the documentation and catalog the material, making it available for use by Vanderbilt’s faculty and the public.

“This is what constitutes museum work, and we have an ethical obligation to do this kind of research,” Hellman says. “It’s very important, because it’s about making us a better institution so that we can serve our communities better.”

![Another View of the Temple of the Sybl in Tivoli, Views of Rome Francesco Piranesi (Italian, ca. 1756–1810), 'Altra Veduta del Tempio della Sibilla in Tivoli' ['Another View of the Temple of the Sibyl in Tivoli'], from Vedute di Roma [Views of Rome], 1761, etching. Sullivan Memorial Collection.](https://i1.wp.com/news.vanderbilt.edu/files/SC0884_Piranesi-Views-of-Rome_edited-scaled.jpg?w=189&h=261&ssl=1)