Ken Galloway’s legacy will continue as he transitions from dean of engineering to full-time faculty member

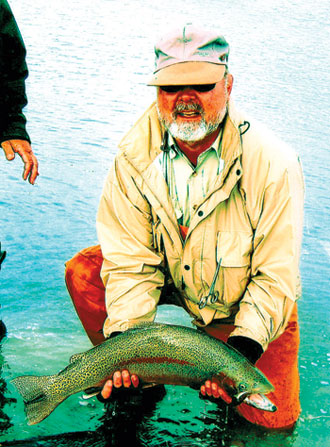

If you ask Ken Galloway what he’s doing on July 1, 2012 – the day he officially transitions from his role as dean of Vanderbilt’s School of Engineering to a full-time faculty member – he is sure to mention his plans for a summer fly fishing excursion in the Western United States. The break will be just what he needs, after 16 years of helming one of the nation’s most upwardly mobile engineering schools and tirelessly serving in national leadership roles in engineering education.

“It’s very hard to stand in the middle of a river with a fly rod trying to fool a trout with feathers and think about anything else at the same time. Almost everything else goes away,” Galloway said in a recent interview, eyeing a prized fishing rod on his office wall as he recalled adventures on the North Platte River in Wyoming.

Just as the river calls to him today, the lure of the rolling hills of Middle Tennessee called him back home nearly 16 years ago to serve as only the seventh dean in the history of the School of Engineering, which marks its 125th anniversary in 2012.

Raised in Columbia, Tenn., Galloway was educated at Vanderbilt and went on to receive his doctorate from the University of South Carolina. At the time he was contacted by a Vanderbilt search committee, he had been chair of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Arizona for 10 years and was pleased by the unexpected opportunity to return to his alma mater as dean. “My wife and I both grew up in Middle Tennessee. It’s a place that’s always been home,” he said.

It was at Arizona that a retired engineering professor introduced Galloway to the quiet solitude of fly fishing in Wyoming. “He kept mentioning, ‘We have to go, we have to go.’ Finally, I went, and I’ve been going ever since.”

Before his tenure at Arizona, Galloway, whose research interests include solid-state devices and semiconductor technology, worked for 12 years with the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology), where he held a number of key positions including chief of the Semiconductor Electronics Division. He also held appointments at the University of Maryland, the Naval Weapons Support Center in Crane, Ind., and at Indiana University.

The engineering school had grown steadily for more than a century when Galloway arrived in 1996 as dean and professor of electrical engineering. An “exemplary manager,” according to co-workers, he assembled and nurtured a team of staff and faculty that has sustained and intensified that trajectory, guiding the school toward new levels of achievement.

One of his primary achievements has been the recruitment, encouragement and support of highly qualified faculty, who in turn have helped attract unprecedented levels of research funding. During Galloway’s tenure, research expenditures from external sources grew from less than $10 million to more than $60 million annually, according to Art Overholser, senior associate dean and professor of biomedical engineering and chemical engineering.

“[rquote]The dean has overseen the recruitment and retention of outstanding young faculty members who will contribute to Vanderbilt’s success for decades to come,” Overholser said.[/rquote] “That will be a long-lasting heritage of Ken Galloway.” Overholser noted that since 2000, 27 School of Engineering faculty members have received National Science Foundation CAREER Awards – four in just the past year.

The physical appearance of the School of Engineering has changed dramatically as well. Thanks to generous alumni and friends of Vanderbilt who heard and answered the call for upgraded facilities, Featheringill Hall – the flagship building of the School of Engineering together with Jacobs Hall – was completed in 2002. It was the first engineering building to be added to the campus since the early 1970s and provided an immediate boost to faculty and student recruiting.

More recently, the university acquired space on Music Row at 16th Avenue South that is now home to the Institute for Software Integrated Systems, one of several centers and institutes under the School of Engineering aegis. The newest effort, the Vanderbilt Initiative for Surgery and Engineering, continues an evolving partnership with Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “It will be a fantastic thing for Vanderbilt,” Galloway said.

But he remains hesitant to pick out particular centers or programs for mention. “You can’t have a favorite child,” he cautioned. In a smaller school, there aren’t as many focus areas, Galloway explained, “but in the areas where we have focused, we’re always one of the best, if not the best, and we’ve had great faculty hires in every department.”

Some of those hires have been fueled by the generous funding of 12 endowed chairs, which are vital to recruiting top faculty, according to Galloway. Eleven of those were awarded within the past 10 years.

Despite many successes, challenges remain. “The faculty needs to grow in size, and research programs need more space in which to grow,” he said. “That means we need more money. But it’s always about people, space and money.”

While at Vanderbilt, Galloway has been a national leader and advocate before Congress for engineering and science education. This year, his contributions led to his induction into the Academy of Fellows of the American Society for Engineering Education. He is the immediate past chair of the ASEE Engineering Deans Council and has served on the ASEE board of directors. He is currently a candidate to become president-elect of the ASEE.

The reputation of the School of Engineering has grown markedly during Galloway’s tenure, not in small part due to his national leadership and visibility. While there are a number of markers of success, U.S. News & World Report’s annual ranking of undergraduate programs has Vanderbilt tied at the No. 34 spot, having ranked in the 50s not so many years ago, according to Overholser. The same is true for graduate programs in engineering, where Vanderbilt is tied for 37th with Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

More notably, when comparing engineering schools based on size, Vanderbilt is now ranked closely with peer schools that have small, academically rigorous engineering programs, such as Cal Tech, Duke, Harvard, Washington University at St. Louis, Yale and Brown.

“We’d like to be in the top 10, but we’ll never be big enough. Size matters in these rankings. But if you look at the size of our student body and the dollars expended per faculty member, we’re darn good,” Galloway said.

Rankings aside, Galloway is most proud of the quality and diversity of the student body and of the graduates the school produces. He is quick to say that the School of Engineering has benefitted as the university’s reputation and quality have grown. But it’s also true that the School of Engineering attracts some of the best and brightest students at Vanderbilt, with more than 4,300 of the most qualified applicants vying for 320 spaces in the engineering and computer science freshman class this year.

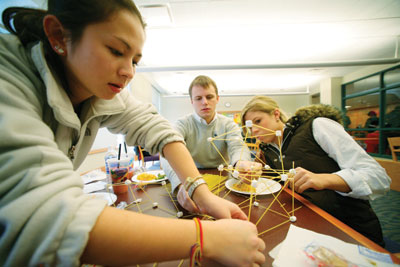

He also points to the fact that engineering majors receive far more than an excellent engineering education. They also receive an outstanding undergraduate education in a much smaller, more personal environment where great teaching is valued as much as cutting-edge research.

“Vanderbilt is not a typical engineering school. We’re not a tech school, so our students have the opportunity to take numerous courses in the College of Arts and Science and to be part of the larger college experience,” Galloway said.

Recruitment of female students is another strong growth area. Women comprise 34 percent of the current student body – about twice the national average for engineering schools, according to Galloway.

How Vanderbilt students fare after they graduate is paramount to the dean. “One of the really enjoyable things about having been dean at Vanderbilt is the opportunity to meet our alumni and to see how well they have used their Vanderbilt educations,” he said. “You see Vanderbilt engineers very often moving into leadership positions. I think that’s because of the broader education they get at Vanderbilt.

“I am always gratified to see what nice people they are and how they’re still very interested in the university. For a dean, that’s one of the most satisfying things.”

The engineering discipline itself has changed dramatically during the past two decades. While Vanderbilt faculty still place emphasis on teaching, their cutting-edge research efforts more and more are focused on “the translation of what we do into useful things for people.”

Galloway’s research interests are many, with an increasing emphasis in nanoscience: shrinking devices while making them faster and faster.

“This research is starting to work its way into multiple products and devices to improve quality of life,” he said. Galloway relishes the opportunity to devote more time to such pursuits.

“It’s been a wonderful experience,” he said. “Vanderbilt is truly a great university. I’ve seen it improve in the time I’ve been here in the quality of students, the quality of faculty and in terms of national recognition. I’m happy to have been part of a very large team that helped make this happen.”

Galloway looks toward his rapidly filling email in-box and then takes a glance at the rod and reel hanging on his office wall.

“Just last weekend, I planned next summer’s trip to Wyoming,” he said. After another energetic year at the helm of the School of Engineering, he eagerly anticipates some quiet moments standing by a beautiful, flowing river.