A shark attack leads to a collaboration that could transform the lives of amputees

It was an overcast June morning at Cap San Blas, Fla., and 16-year-old Craig Hutto had nothing but fishing on his mind. Situated about 50 miles south of Panama City on a peninsula in the Gulf of Mexico, the quiet beach community made for a perfect vacation spot for Craig and his Lebanon, Tenn., family.

The beach was nearly deserted, but the fish were biting. And so the lanky teen, with his 25-year-old brother Brian close behind, waded out through chest-deep water toward a sand bar, fishing poles held aloft.

It was just then that the younger Hutto felt something bump against his left leg. The murky water gave no signs as to what lurked below. “I jumped back and said, ‘What was that?’” he said.

In the next instant, Hutto felt intense pressure on his right thigh, and a whoosh of waves as he was dragged underwater in the direction of the open sea.

“I remember telling myself, ‘This is a dream. You have to wake up right now,’” Hutto said.

Hutto resurfaced and began screaming for help. His brother swam to his rescue, frantically striking the shark with his fishing rod, which seemed to have no effect. Desperate, Brian Hutto wrapped his arms around his brother and began swimming toward shore, pulling against the weight of the shark still attached to his leg.

“The whole time the shark was biting up and down, but I couldn’t feel anything except for an intense shaking and pressure,” Hutto said.

“[rquote]I basically just went into shock. I tried to stick my hands in the shark’s mouth to pry it off, and I just remember pulling my hands out of the water and they were shredded to pieces.”[/rquote]

The shark continued to bite with ferocity, while Brian Hutto struggled to pull his brother to shore. By this time, their parents and a crowd of onlookers had gathered on the sand, helplessly watching as the struggling forms carved a crimson swath of blood in the sparkling water. It wasn’t until Brian Hutto began punching the shark in the snout that it at last let go and swam back to sea, disappearing into the salty depths.

The brothers collapsed onto the sand, exhausted and stunned. The flesh on Hutto’s leg was ragged, bone and tissue stripped away, the femoral artery severed and spurting.

Miraculously, three medical professionals were on the beach that day and quickly rushed to Hutto’s side. They made makeshift tourniquets, applying pressure to stop the bleeding. Doctors would later estimate that he lost nearly half the blood in his body. Brain damage was an immediate concern, if he even lived.

An ambulance arrived, then a helicopter. When Hutto awoke in a Panama City hospital, he begged his mother not to let the doctors take his leg.

But in his heart he knew the truth. His leg was already gone.

Observers estimated that Hutto had been attacked by a six- to eight-foot-long bull shark, an aggressive breed known for trolling shallow warm waters where humans often swim. In fact, about 50 miles away and three days earlier, a young woman had been killed by a bull shark. Media outlets bombarded the family with calls. And every time Hutto awoke, he asked his caregivers, “Tell me the truth – am I going to survive?”

Two weeks later, Hutto was at Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, where he spent several weeks enduring surgeries to repair the nerve and tendon damage in his hands. With his right leg now amputated several inches above the knee, Hutto would return to high school just a month after the attack to begin his senior year in a wheelchair, his hands still bandaged.

“After the attack, I was depressed and not the most fun person to be around,” Hutto said. “But early on Brian told me that I needed to quit being a baby and suck it up. It was great that he could be so nice like that,” he added with a wry smile. “He told me I had gone through the worst and was still alive, and that’s what I needed to be thankful for. That’s when feeling sorry for myself went out the door. And basically I haven’t looked back since.”

Fast-forward six years, and Hutto is a 6-foot-4-inch 23-year-old who’s working his way through Middle Tennessee State University’s nursing school. His job? Lab assistant in the Olin Hall laboratory of Vanderbilt mechanical engineering professor Michael Goldfarb. The two were introduced by the technician who fitted Hutto for his first prosthetic leg. Goldfarb was looking for an amputee willing to help him test a robotic artificial leg he was developing. Hutto fit the bill and has been employed there ever since.

“It’s an awesome job for me,” said Hutto, who is scheduled to graduate in December from MTSU. “When I’m not testing the leg, I am reading up on studies and looking for published papers. My main job is to test the leg’s functions and give them feedback and let them know the issues a person using a prosthetic leg faces on a daily basis.”

Watch video of Craig Hutto demonstrating the prosthetic leg.

Goldfarb’s team’s creation, which they unofficially refer to as the Vanderbilt Powered Prosthesis, is constructed of aluminum alloy and weighs about nine pounds. It is unique in that it is embedded with programmable software that responds to human movements and reacts accordingly. Unlike its non-powered counterparts, the leg has a “mind of its own” that senses when the user is trying to sit, stand, walk or traverse different terrains.

“This leg is capable of understanding the intent of the user in a very short time period by using a wide array of mechanical sensors,” said Research Assistant Professor Huseyin Atakan Varol, who has been working with Goldfarb to perfect the leg for five years. “It generates behaviors at the knee and ankle joints that closely mimic the behavior of a healthy limb.”

Falls are common for amputees because traditional prosthetics don’t transition well from flat surfaces to hills or stairs. Goldfarb believes this leg will resolve those issues.

“[rquote]The leg is able to do everything that you normally would do during the day,” Goldfarb said.[/rquote] “It can do transitions from sit to stand, it can shuffle, move from side to side, walk at different speeds and navigate varying types of terrain.”

The leg uses advanced transmission mechanisms and electrical motors to move the knee and ankle joints, while being remarkably lightweight and nearly silent.

“The powered prosthesis has many more capabilities than the passive leg I have right now,” Hutto said. “I have to rely on the power in my sound leg, which can get tiring in some situations.”

Hutto has been an invaluable asset to the research team, said Goldfarb, who plans to release the prototype leg soon to a manufacturer. He estimates the cost will be about the same as a traditional prosthetic and most insurance companies will cover it.

“Craig deserves a lot of credit for his contributions to this,” said Goldfarb. “He tells us when there is something that is not going to work, or when there is some function that an amputee will not tolerate. We are always getting Craig to push it hard and see what needs to be better. When he really likes a behavior or there is something that surprises him, those are rewarding moments for us.”

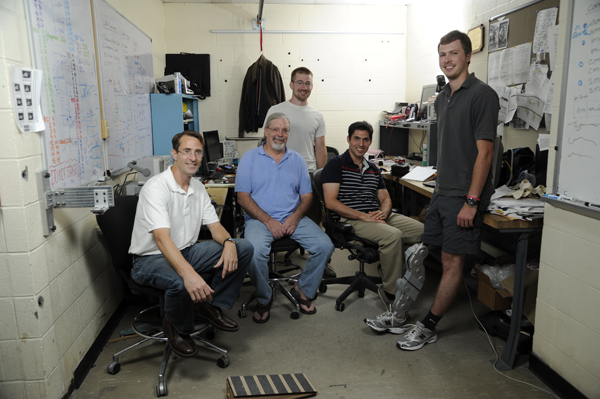

Integrally involved in the leg’s development are research engineers Jason Mitchell and Don Truex, and graduate student Brian Lawson. The team has seen the leg through seven different incarnations and has spent countless hours perfecting it.

“The powered knee and ankle prosthesis will demonstrate to the industry that intelligent powered prostheses are technologically feasible,” Varol said. “Presumably, it might force the prosthetics industry to be more innovative and bring new and better products to the market. The potential to help those who need it most is very encouraging, and it provides the motivation for us during the times when you are stuck with technical problems.”

Had Hutto not experienced the shark attack, he would never have met Goldfarb, Varol and the rest of the team with whom he has now spent countless hours in the Olin Hall laboratory. He also likely would not have pursued a career in medicine, he said.

“Computers have always interested me. [rquote]I planned to do computer science. Then this happened, and it was clear to me: Medical personnel saved my life, Hutto said. I need to give back.[/rquote]”

Hutto hopes to get a job after graduation at the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, the same hospital where he received care in the weeks after the 2005 attack. Later, he plans to continue his education and become a certified registered nurse anesthetist.

“It’s scary for a child to undergo surgery,” he said. “I want to be the one to make that less traumatic for them – to be their lifeline.”

Hutto has vacationed in the Florida panhandle more than a half-dozen times since he lost his leg, and has even returned to the site of the attack. He’s regained most of the use of his hands and fingers, though they are laced with scars and still have some numbness.

In his final months of college, Hutto is president of the inter-fraternity council at MTSU. He shares a house with three roommates, and when he isn’t working or studying, he hits the gym or plays disc golf with his friends. His parents, who live nearby, insist he should visit more often.

In other words, life is good.

But the past is not completely behind him. Hutto has told his story many times – to television crews and reporters, to school groups, to friends, family and strangers. And chances are, he’ll tell it more times still.

“I share what happened to me because that helps people,” he said. “I was very fortunate that I have the family and friends that I have and my faith, which I rely on a lot. I was one of the lucky ones and the whole thing has changed me as a person. It made me realize I don’t really need to sweat the small stuff anymore.”

Watch video of Craig Hutto demonstrating the prosthetic leg.